Joris Ivens'eerste echtgenote had een avontuurlijk leven. Haar avant-garde foto's in de jaren '20 en '30 hebben naam gemaakt. Het Parijse museum Jeu de paume toont tot 27 september haar oeuvre. Gastconservator Michel Frizot werpt een nieuw licht op haar werk en invloed. Volgens hem is zij de belangrijkste fotojournaliste in het interbellum.

Krull's eerste baanbrekende fotoboek is ‘Métal’, dat in de maanden na de première van Ivens’ De brug op 5 mei 1928 verscheen. Ivens’ film en Krull’s foto’s vertonen sterke overeenkomsten vanwege de opvallende standpunten, diagonaal, in vogelvlucht- of kikvorsperspectief, zonder tussenkomst van menselijk drama of een verhalend element, met uitsluitend de focus op het harde metaal. Het zijn daarom beide iconen van het modernisme. Ivens had Krull in 1922 tijdens zijn studie in Berlijn leren kennen in de kring van zijn vriend Arthur Lehning. Al in haar Berlijnse periode liet Krull zien roldoorbrekende foto’s te maken met onderwerpen die men destijds niet vond passen voor vrouwelijke fotografen: naakte vrouwen die elkaar zoenen. Ze had toen al heel wat levenservaring achter de rug met o.a. deelname aan de revolutionaire Radenrepubliek, een aantal afgebroken liefdesrelaties en abortussen en een tocht naar het congres van de Communistische Internationale in Moskou, die eindigde in gevangenschap. Ivens was voor haar een stabiele factor en introductie in de ondernemerswereld. Ze waren smoorverliefd en in 1925 trok Krull mee naar Nederland, naar Nijmegen en Amsterdam. In de Amsterdamse haven begon ze met het fotograferen van havenkranen, een onderwerp dat haar sterk trok en door haar ook in de havens van Rotterdam, Antwerpen en Marseille werd vastgelegd. Het werk van de Hongaarse fotograaf Laszlo Moholy-Nagy vormde daarbij een inspiratiebron. Toen Ivens in januari 1928 de opnames startte van de hefbrug in Rotterdam trok Krull een paar maal mee en fotografeerde Ivens tijdens zijn halsbrekende toeren. Hoewel zij in maart-april in Parijs en Amsterdam met elkaar trouwden, was hun liefdesrelatie al afgelopen. Het belette hen niet om artistiek verder te gaan.

Krull maakte ook foto’s bij Regen, Branding en Etudes des mouvements, dat begint met opnames vanuit haar appartement in Parijs.

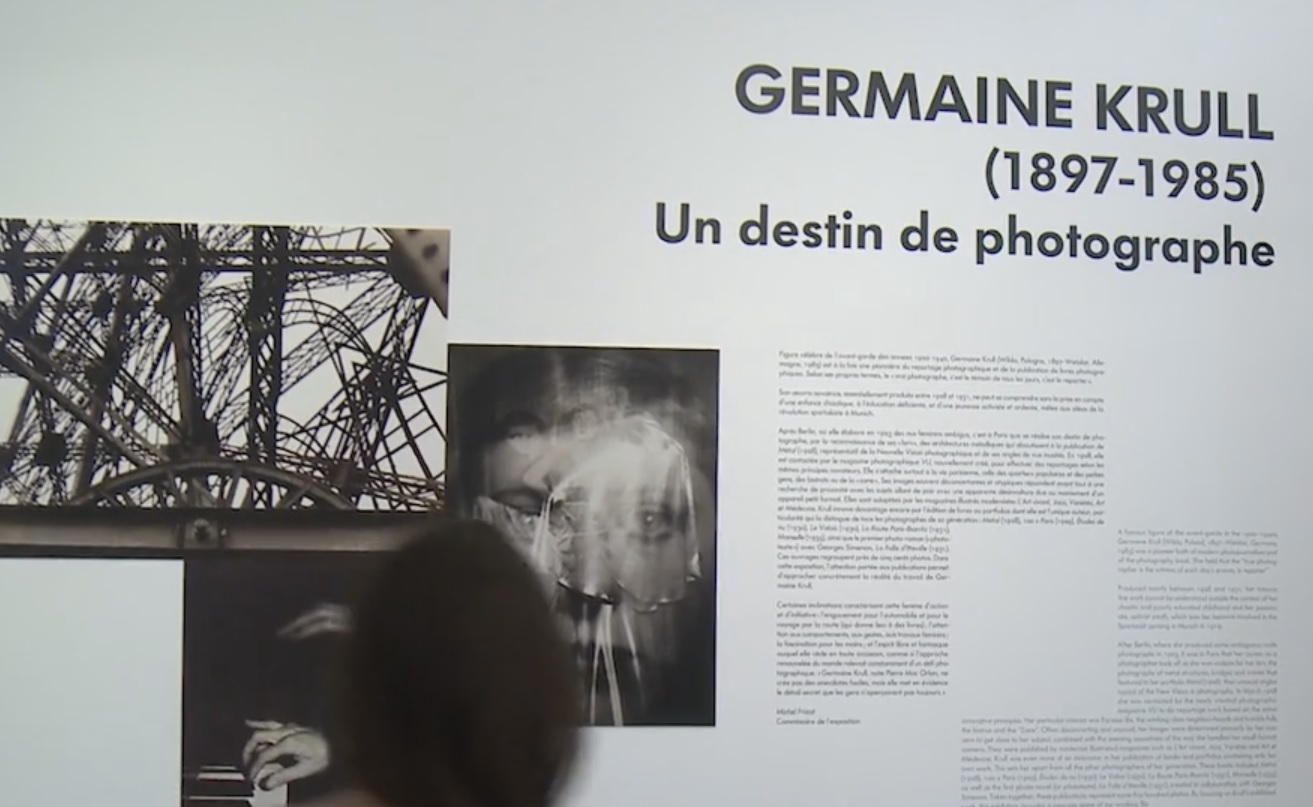

Musée Jeu de paume schrijft over de expositie:

“Germaine Krull (Wilda-Poznań, East Prussia [after 1919: Poland], 1897-Wetzlar, Germany, 1985) is at once one of the best-known figures in the history of photography, by virtue of her role in the avant-garde’s from 1920 to 1940, and a pioneer of modern photojournalism. She was also the first to publish in book form as an end in itself.

The exhibition at Jeu de Paume revisits Germaine Krull’s work in a new way, based on collections that have only recently been made available, in order to show the balance between a modernist artistic vision and an innovative role in print media, illustration and documentation. As she herself put it – paradoxically, in the introduction to her Études de nu (1930) -, ‘The true photographer is the witness of each day’s events, a reporter.’

If Krull is one of the most famous women photographers, her work has been little studied in comparison to that of her contemporaries Man Ray, László Moholy-Nagy and André Kertész. Nor has she had many exhibitions: in 1967, a first evocation was put on at the Musée du Cinéma in Paris, then came the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn, in 1977, the Musée Réattu, Arles, in 1988, and the 1999 retrospective based on the archives placed at the Folkwang Museum, Essen.

The exhibition at Jeu de Paume focuses on the Parisian period, 1926-1935, and more precisely on the years of intensive activity between 1928 and 1933, by relating 130 vintage prints to period documents, including the magazines and books in which Krull played such a unique and prominent role. This presentation gives an idea of the constants that run through her work while also bringing out her aesthetic innovations. The show features many singular but also representative images from her prolific output, putting them in their original context.

Born in East Prussia (later Poland) to German parents, Krull had a chaotic childhood, as her hapless father, an engineer, travelled in search of work. This included a spell in Paris in 1906. After studying photography in Munich, Krull became involved in the political upheavals of post-war Germany in 1919, her role in the communist movement leading to a close shave with the Bolsheviks in Moscow. Having made some remarkable photographs of nudes during her early career, noteworthy for their freedom of tone and subject, in 1925 she was in the Netherlands, where she was fascinated by the metal structures and cranes in the docks, and embarked on a series of photographs that, following her move to Paris, would bear fruit in the portfolio Métal, publication of which placed her at the forefront of the avant-garde, the Nouvelle Vision in photography. Her new-found status earned her a prominent position on the new photographic magazine VU, created in 1928, where, along with André Kertész and Eli Lotar, she developed a new form of reportage that was particularly congenial to her, affording freedom of expression and freedom from taboos as well as closeness to the subject – all facilitated by her small-format (6 x 9 cm) Icarette camera.

This exhibition shows the extraordinary blossoming of Krull’s unique vision in around 1930, a vision that is hard to define because it adapted to its subjects with a mixture of charisma and empathy, while remaining constantly innovative in terms of its aesthetic. It is essential, here, to show that Krull always worked for publication: apart from the modernist VU, where she was a contributor from 1928 to 1933, she produced reportage for many other magazines, such as Jazz, Variétés, Art et Médecine and L’Art vivant. Most importantly, and unlike any other photographer of her generation, she published a number of books and portfolios as sole author: Métal (1928), 100 x Paris (1929), Études de nu (1930), Le Valois (1930), La Route Paris-Biarritz (1931), Marseille (1935). She also created the first photo-novel, La Folle d’Itteville (1931), in collaboration with Georges Simenon. These various publications represent a total of some five hundred photographs. Krull also contributed to some important collective books, particularly on the subject of Paris: Paris, 1928; Visages de Paris, 1930; Paris under 4 Arstider, 1930; La Route Paris-Méditerranée, 1931. Her images are often disconcerting, atypical and utterly free of standardisation.

An energetic figure with strong left-wing convictions and a great traveller, Krull’s approach to photography was antithetical to the aesthetically led, interpretative practice of the Bauhaus or Surrealists. During the Second World War, she joined the Free French (1941) and served the cause with her camera, later following the Battle of Alsace (her photographs of which were made into a book). Shortly afterwards she left Europe for Southeast Asia, becoming director of the Oriental Hotel in Bangkok, which she helped turn into a renowned establishment, and then moving on to India where, having converted to Buddhism, she served the community of Tibetan exiles near Dehra-Dun.

During all her years in Asia, Krull continued to take photographs. Her thousands of images included Buddhist sites and monuments, some of them taken as illustrations for a book planned by her friend André Malraux. The conception of the books she published throughout her life was unfailingly original: Ballets de Monte-Carlo (1937); Uma Cidade Antiga do Brasil; Ouro Preto (1943); Chieng Mai (c. 1960); Tibetans in India (1968).

In her photojournalism, Krull began by focusing on the lower reaches of Parisian life, its modest, working population, the outcasts and marginal of the “Zone,” the tramps (subject of a hugely successful piece in VU), Les Halles and the markets, the fairgrounds evoked by Francis Carco and Pierre Mac Orlan (her greatest champion). The exhibition also explores unchanging aspects of her tastes and attachments: the love of cars and road trips, the interest in women (whether writers or workers), the fascination with hands, and the free, maverick spirit that drove her work and kept her outside schools and sects.

The works come from a public and private collections including the Folkwang Museum, Essen; Amsab, Institute for Social History, Ghent; the Ann and Jürgen Wilde Foundation, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich; The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York; the Centre Pompidou, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris; the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris; the Collection Bouqueret-Rémy; the Dietmar Siegert Collection.”